When almost five million pieces of Lego escaped into the sea off the coast of Cornwall, the tiny, colourful figurines that soon amassed on the beaches, quickly became a treasure trove for beachcombers.

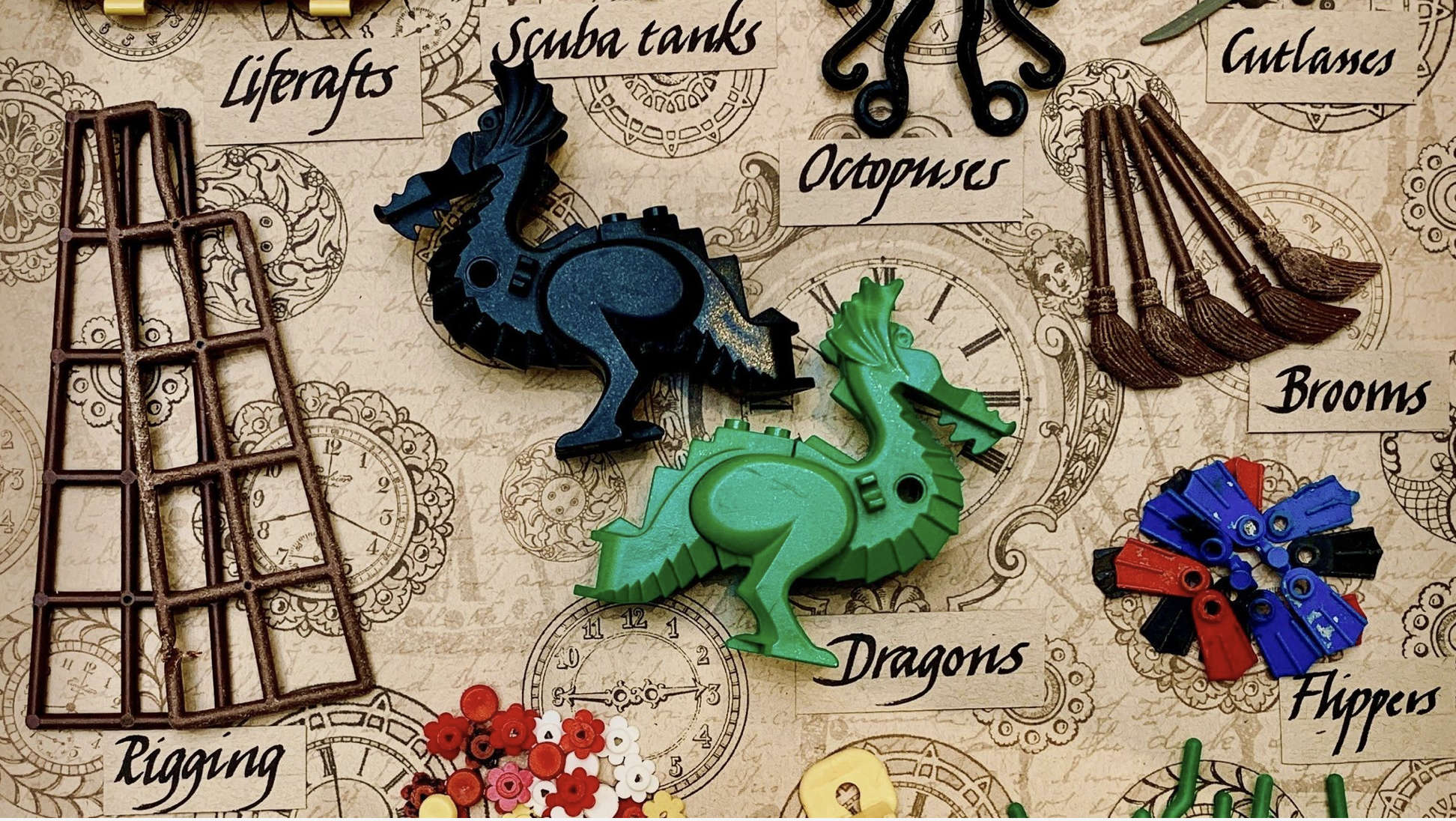

Many of the pieces, coincidentally, were sea-themed: flippers, octopuses, life jackets, spear guns, cutlasses, sharks and scuba tanks; thousands of them making their way to the shoreline to be found bobbing in rockpools and strewn across the sand. There were also witches hats, wands, brooms and more.

The Tokio Express was a cargo ship bound for New York in the US after setting sail from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. It was 13 February 1997 when it all but overturned about 20 miles off Land's End, the container of Lego one of just 62 that fell into the water. Twenty-five years later, its tiny plastic passengers can still often be found washed up on the shore, many barely unchanged by the passage of time and a life under the waves.

Tracey Williams was living in Devon when the shipping crate spilled, and this is where she first started noticing the Lego. The toys had captured the imaginations of residents for miles around; like the Panini football sticker albums that were playground staples of the 1970s, '80s and '90s, they became collectibles - with the rare green dragons (the container had held just 514, compared with 33,427 black dragons) among the biggest prizes. Black octopuses were the "holy grail" as they blended in with the seaweed so were difficult to spot; Williams found her first in 1997 but didn't discover another for 18 years.

After moving inland, she forgot about the Lego for a while. But after returning to Cornwall in 2010, she discovered Lego items during her very first trip to the beach there. What started as a collecting exercise turned into an exploration of our oceans, the rubbish that ends up in the water, and the lingering legacy of plastic.

"I thought it was amazing that it was still washing up all these years later," she says. "It started off as a bit of fun. But over the years, it made me realise the amount of plastic in the ocean and buried in the sand."

Williams started to record her findings, at first setting up a Facebook page and later other social media accounts on Twitter and Instagram. Thousands of people got in touch, she says, sharing details of their own beachcombing treasures.

She now tells the story in a new book, Adrift: The Curious Tale Of The Lego Lost At Sea.

"It was interesting to start mapping it and see how far it had travelled," she says. Lego pieces were found on the Gower peninsula in Wales, County Kerry in Ireland, Kent and Guernsey. Some made their way to France and Belgium, some even returned to Holland.

"It was thought at the time that half the Lego floated and half sank - that's a bit simplified, but pretty much," says Williams.

"What we're realising is that even the Lego that sank is now starting to wash ashore and it's gradually drifting along the seabed. I think it shows us how long plastic lasts and how far it travels and what happens to it as it breaks down."

Tim Brooks, vice-president of environmental sustainability at the Lego Group, is interviewed in the book, and tells Sky News the company is "passionate about keeping Lego bricks out of nature, and we don't ever want Lego bricks to end up in the sea".

He adds: "The Lego Group is very serious about taking care of the planet and we have a bold sustainability strategy that aims to leave a positive impact on the planet for children to inherit."

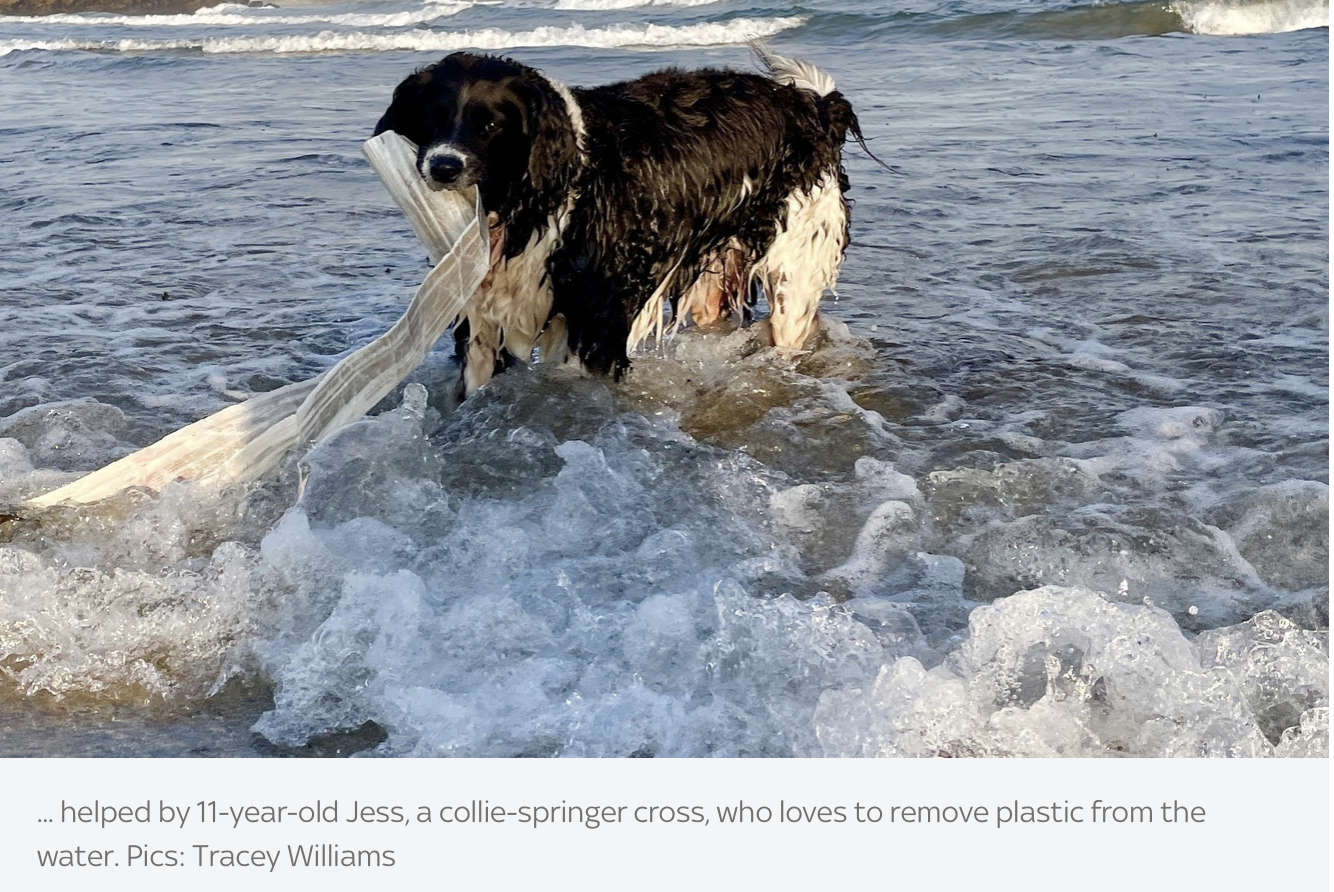

You will find Williams, accompanied by her dog Jess, combing the beach near her home on the north coast of Cornwall first thing each morning. At the moment, following a seaweed invasion that brought lots of rubbish with it, this can be the first of up to four trips a day, she says, although points out that there is not always such a need.

"I've picked up about 2,000 strips of rubber, which we think might be from lobster pots or crab pots, but I don't know. Things like dental floss and diabetes lancets, it's all stuff that I guess has been flushed down the loo in years gone by and it's still all down there. Some of it is 40 years old."

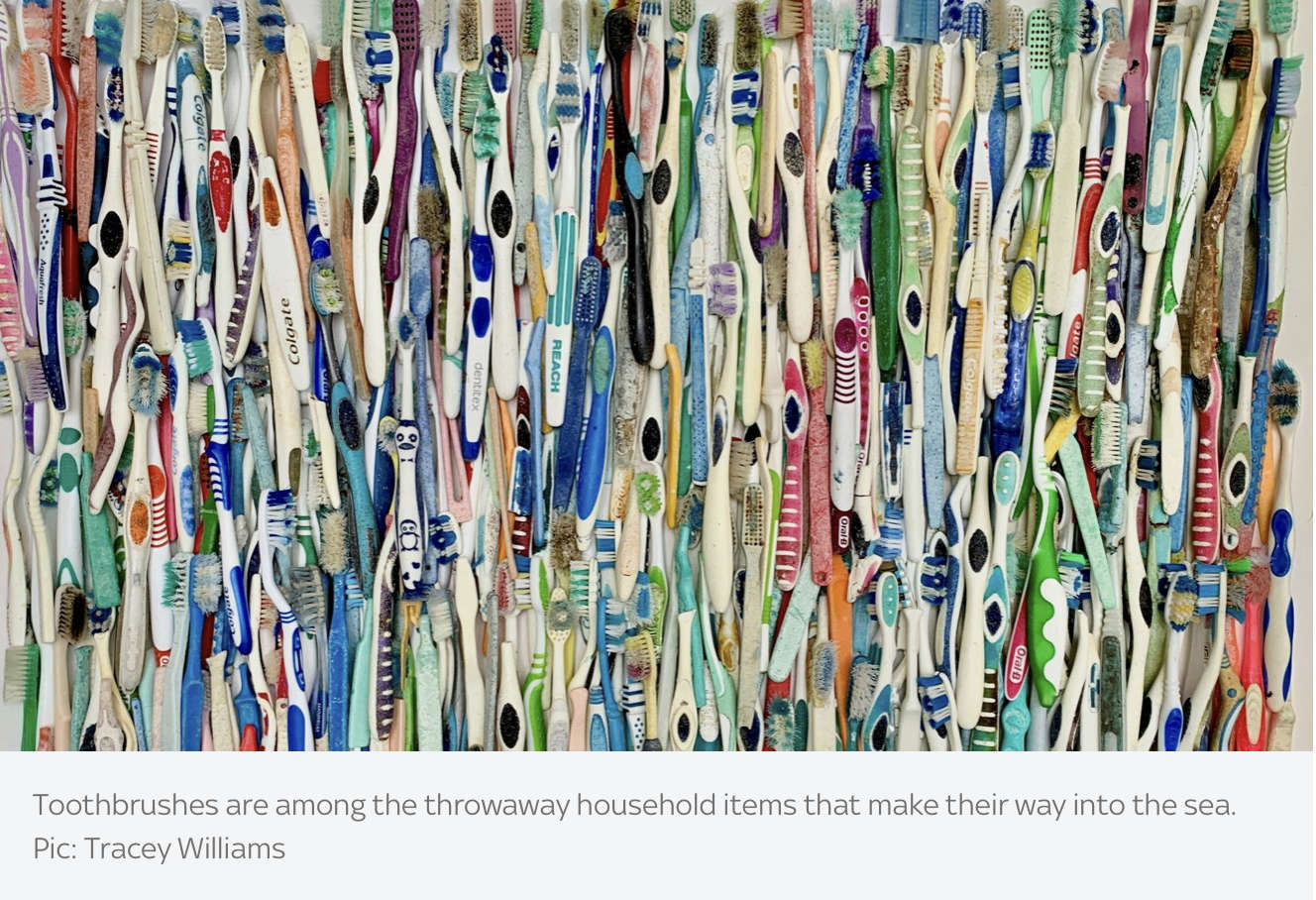

During her beach cleans, Williams has uncovered all sorts of items: pens, toothbrushes, coat-hangers and of course, plastic bottles. She amassed a colourful collection of lids from Smartie tubes that are "50 to 60 years old". Unsurprisingly, much of the rubbish now is COVID-related.

She has thousands of Lego items stored away at home, with plans for an exhibition one day, but doesn't keep much else.

"I try and find a home for it," she says of the rest of the rubbish she finds. "I pass a lot of the plastics on to local artists who use it to raise awareness of marine debris. We recycle what we can. Buckets and spades, good quality items, we'll take to charity shops and so on."

Adrift is filled with beautiful images of Williams' finds which evoke feelings of nostalgia; the long-forgotten childhood toys that have lived on in a different world. She hopes it will raise awareness of the damaging effects of plastic in our oceans in a way that doesn't make people feel afraid or like they are being blamed.

"I think what the Lego has done, it's allowed us to sort of tell the story of plastic in the ocean in a way that's not too frightening and in a way that people can identify with. I do have some horrible images, upsetting images, of birds strangled in rope and I think sometimes it can be so upsetting that you don't want to look at it. I get that. It is an upsetting subject, but what I've tried to do is tell the story of ocean plastic in a way that is not so upsetting."

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, she says. "Are toothbrushes beautiful?" One toothbrush is rubbish, perhaps, but when you see dozens lined up together it makes for a piece of thought-provoking art. Some photos show typical rubbish - crisp packets, bottles, fishing lures and tattered flip-flops - while others feature the symbols of many childhoods: cereal packet toys, a Garfield phone, My Little Ponies, as well as the Lego.

Growing up in the '90s, I collected Trolls while my sister had Polly Pockets, I tell Williams. These too have been found washed up in Cornwall.

"I don't know what happened to all my childhood toys," Williams says. "Do you know what happened to yours? It makes you suddenly think, 'well, where are they?' Are they in landfill somewhere? Is the landfill going into the sea? It makes you think, 'I had all these things, but where did they all end up?'"

The Garfield phone wasn't a find in Cornwall, but rather in Brittany, on the northwest coast of France. Williams documents other cargo spills in Adrift - including the famous 1992 rubber duck escape in the North Pacific - and tells how the Garfield phone featured wasn't a one-off; the devices mysteriously started washing up on beaches in Brittany in the 1980s, she says. The source? A lost shipping container of the phones which was eventually found lodged in a sea cave.

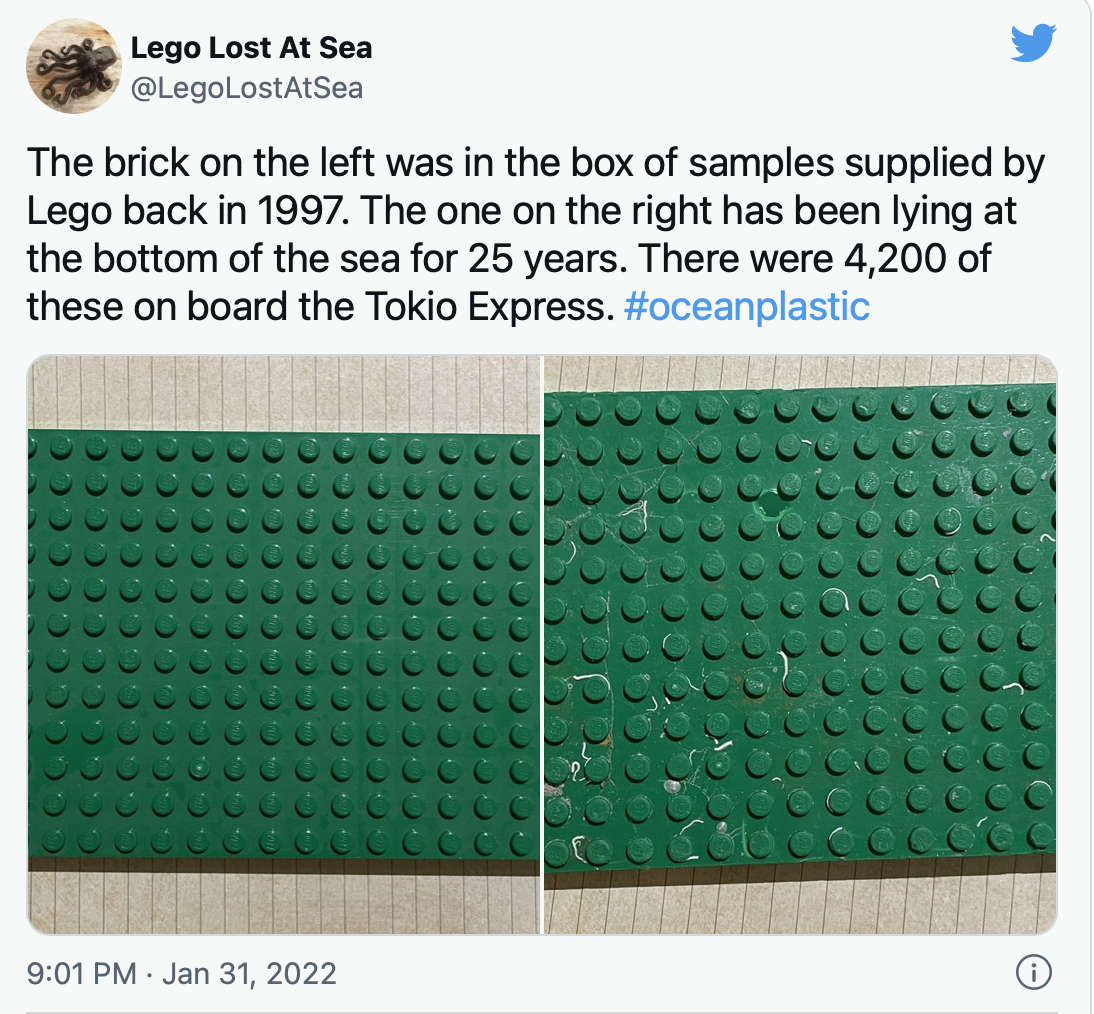

As part of her research, Williams teamed up with scientists at the University of Plymouth to test how long Lego could last in the sea. Between 100 and 1,300 years, they concluded. She recently shared two side-by-side photos of Lego bricks on social media, one a sample provided in 1997, the other discovered in a fisherman's net at the end of January.

"There's not much difference between them," she says. "[The brick from the spill] has got a few marine creatures living on it but it's still in perfect condition.

"I think what's shocking me now is realising how much [plastic] is actually lying on the seabed because I think very often you only really see and hear about the plastic that washes ashore. If there's a cargo spill, there's usually reports of what's washing up but there's never any mention of all the items that sank to the bottom of the sea.

"I think it's assumed that it's almost gone forever and lost without trace. But we know from the Lego that it's all still there."

Adrift: The Curious Tale Of The Lego Lost At Sea, by Tracey Williams, is out now

World's Tallest And Shortest Women Meet For First Time To Celebrate Guinness World Records Day 2024

World's Tallest And Shortest Women Meet For First Time To Celebrate Guinness World Records Day 2024

Shannen Doherty: Beverly Hills, 90210 Star Dies Aged 53

Shannen Doherty: Beverly Hills, 90210 Star Dies Aged 53

Olivia Dean, Chaka Khan, Terence Trent D’Arby And Dionne Warwick Confirmed For Star-Studded Love Supreme

Olivia Dean, Chaka Khan, Terence Trent D’Arby And Dionne Warwick Confirmed For Star-Studded Love Supreme

Boom Shakes The Room — Explosion of Colour And Happy Vibes At Spellbinding Gathering

Boom Shakes The Room — Explosion of Colour And Happy Vibes At Spellbinding Gathering

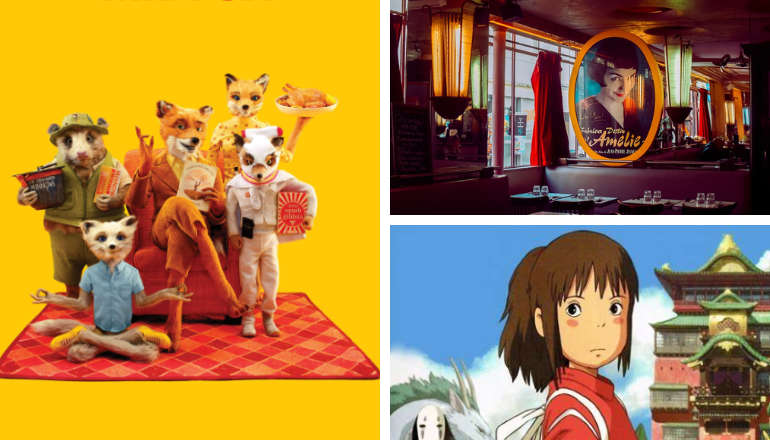

Struggling To Sleep? New Research Names The Movies That Will Help

Struggling To Sleep? New Research Names The Movies That Will Help