Reality television lines have become blurred since Endemol brought Big Brother kicking and screaming to UK screens at the turn of the Millennium.

'Nasty' Nick Bateman and a hastily assembled jury perched around a table in the BB abode during the summer of 2000.

The conniving housemate’s best laid plans and schemes had finally unravelled on day 35 of the series, when chief bloodhound — and eventual winner — Craig Phillips tracked the scent responsible for millions of viewers screaming vicious curse words at their screens for the past five weeks.

At the time it seemed to matter, with loveable Scouse scallywag Craig the perfect foil for dastardly antagonist Nick.

Until then those living at close quarters were unable to recognise the deviant’s mischievous antics, adding to nationwide exasperation.

Tabloids stirred the pot, calling for Bateman to be deported and naming him ‘the most hated man in Britain.’

The bar continues to be raised

Today Nick’s indiscretions wouldn’t generate a ripple amongst his ravenous modern day counterparts, many of whom play to cameras like neglected toddlers.

What was once a genre grounded in the factual has evolved into a scripted sermon of soap opera rhetoric, aimed at advertising products and stirring up social media.

That's not to say modification wasn't needed, with people growing weary of 24-hour feeds dominated by snoozing, mastication and repetitive yakking.

Even the juicy bits were eventually rendered impotent by time-delay and on-the-spot editing, ensuring they were reserved as flesh for the evening highlight reel.

Success inevitably spawns imitation

Just as Big Brother and The Real World blazed a trail for Celebrity Love Island and I'm a Celebrity, so The Osbournes unlocked the door for the curiously watchable Hogan Knows Best and less appealing What Katie Did Next.

It came full circle at the end of the ‘noughties,’ with the rise of exclusively scripted (un)reality TV, where scenes were set up solely for the satiation of a wide-eyed audience.

The inception of the undoubtedly entertaining Made In Chelsea in 2011 allowed viewers to peek into a fantasy universe presenting equal parts cocktails and cock-tales.

The Hello magazine of the small screen, an ever-evolving cast of characters parade around South West London, their tail feathers gleaming, with not a hint of hardship or a hair out of place. All within the confines of a painstakingly conceived goldfish bowl.

The appeal lies in the jet-set lifestyles enjoyed by a gaggle of coiffured rich kids — heirs to corporations who share body fluids and Jacuzzis in a state of perpetual down time.

It's fun, but reality? The veneers that adorn the collective casts' faces are less phoney than the narratives that play out, act by act, for the consumption of invested voyeurs.

Even so, SW3’s brand of entertainment is indisputably several notches above the ‘Real Housewives’ franchise and retains a stylistic value courtesy of engaging caricatures and slick presentation.

The continued saturation of the reality genre amplifies salacious concepts to provide shock value — the lifeblood of these productions.

A childish public school graduate scribbling names onto scrunched up A5 sheets torn from a notepad no longer gratifies the lust; numbed by years of hyperbole and recurring adaptations of good vs evil.

In 2022 reality TV is a three dimensional comic book, ideal for pickling the psyche and providing aesthetically captivating colour schemes. For Gotham, Keystone and Metropolis read Chelsea, Essex and Gwrych Castle in Wales.

How much further can the envelope be shifted? Only time will tell. For the next clutch of fame-hungry wannabes and gluttonous viewers nothing seems taboo.

Prepare not to be shocked… in the most shocking way possible.

World's Tallest And Shortest Women Meet For First Time To Celebrate Guinness World Records Day 2024

World's Tallest And Shortest Women Meet For First Time To Celebrate Guinness World Records Day 2024

Shannen Doherty: Beverly Hills, 90210 Star Dies Aged 53

Shannen Doherty: Beverly Hills, 90210 Star Dies Aged 53

Olivia Dean, Chaka Khan, Terence Trent D’Arby And Dionne Warwick Confirmed For Star-Studded Love Supreme

Olivia Dean, Chaka Khan, Terence Trent D’Arby And Dionne Warwick Confirmed For Star-Studded Love Supreme

Boom Shakes The Room — Explosion of Colour And Happy Vibes At Spellbinding Gathering

Boom Shakes The Room — Explosion of Colour And Happy Vibes At Spellbinding Gathering

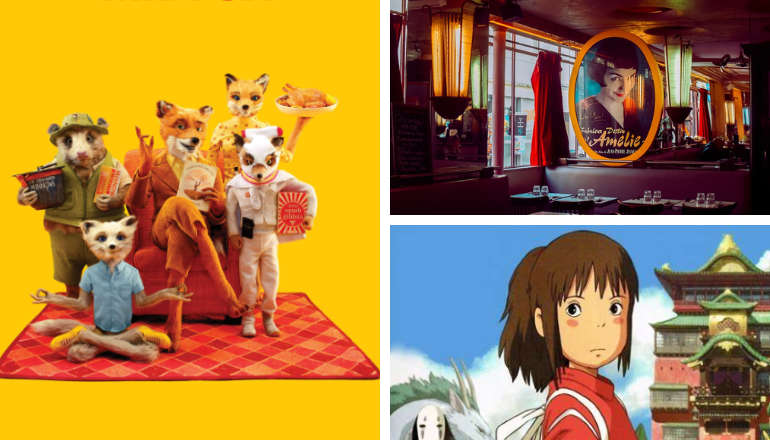

Struggling To Sleep? New Research Names The Movies That Will Help

Struggling To Sleep? New Research Names The Movies That Will Help

Comments

Add a comment