With an estimated four million children living in poverty in the UK, lack of full vaccine cover due to low second vaccine rates could expose some to more serious disease.

Children and young adults living in poverty in the UK who haven't had the second dose of the MMR vaccine could be at risk of more serious forms of the disease says University of Brighton microbiologist and Fellow of the Institute of Biomedical Science Dr Sarah Pitt.

She said that the current cost of living crisis and its impact on parent’s ability to afford nutritious food could put more children at risk from the disease:

“In the UK, most children experiencing severe illness as a result of measles infection are likely to receive good hospital care. However, it is important to note the effect of a healthy balanced diet on the ability to fight infections.

"We know that over four million children in the UK are living in poverty and some are so malnourished that they are being admitted to hospital. So those children might be at higher risk of severe measles, although they should get the treatment they need.”

“It is worth noting how easily the measles virus can spread. When we think about our lived experience of COVID-19 , we know that it is very infectious. Virologists estimate that someone with the current Omicron JN.1 version of COVID could infect around 5 other people. For measles, that figure is 15.”

Because the measles virus is so infectious, 93% of children need to have both doses of the MMR vaccine to ensure the virus does not spread. The average vaccination rate for second dose of MMR across England is around 84%. Having both MMR vaccinations will give long-lasting protection against measles, mumps and rubella.

Dr Pitt said while most people who get measles will recover with no side-effects, those who are clinically vulnerable or who are generally not very healthy are much more likely to develop chest infections.

“One of the reasons for the global measles vaccination programme was the high rates of a pneumonia seen in malnourished children in lower income countries.

"They were at very high risk of developing a severe chest infection which was often fatal where no treatment was available. Before the introduction of the vaccine, it was estimated that at least two and a half million children died from the complications of measles each year across the world.

"Thanks to the World Health Organisation’s vaccination programme, this was reduced to about 128,000 in 2021.”

She said that the successful vaccination campaign since the 1960s means that many people have not witnessed the potentially devastating outcome of the disease:

“In the UK, we have been vaccinating children against measles since the late 1960s and we eliminated measles in 2016. So, I think people have forgotten just how nasty the virus can be in some people.

"Measles itself is miserable – you feel awful, have a sore throat, itchy eyes, earache, very high temperature and a blotchy rash. That is bad enough, although most children get better. However, some children develop side-effects such as chest infections and brain disease. As we are seeing from the news, sometimes, the worst forms of measles need treatment in hospital.”

Dr Pitt said:

“It is very important to have both doses for the vaccine to work properly. There is a gap between doses. The first is given when the child is around 12 months and the second is not due until they are 3 years and 4 months. So, I think that perhaps parents don’t realise the importance of the second dose because of that gap.”

It’s not only children who may need the second dose:

“At the moment, the NHS is targeting children aged 5-11 years for the second dose as primary school children are the ones developing measles. But teenagers and young adults who have not had the second dose should also have it as soon as possible. Anybody who are unsure of the vaccination status should contact their GP.”

Funding Available For Tree Planting In Chichester District as National Tree Week Begins

Funding Available For Tree Planting In Chichester District as National Tree Week Begins

West Sussex Firefighters And Emergency Services Carry Out Training Exercise In Chichester Harbour

West Sussex Firefighters And Emergency Services Carry Out Training Exercise In Chichester Harbour

Shoreham Lifeboat’s Festive Look Boosted By Family-Run Business

Shoreham Lifeboat’s Festive Look Boosted By Family-Run Business

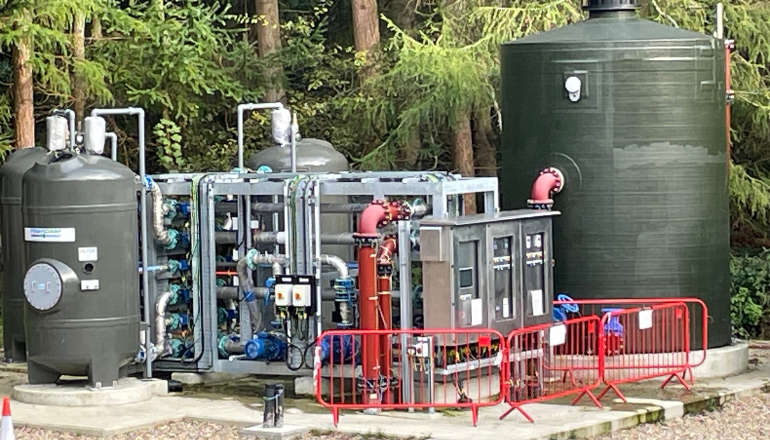

Final Touches Being Made To £2m Sussex Wastewater Site Upgrade

Final Touches Being Made To £2m Sussex Wastewater Site Upgrade

AllSaints Founder To Host Sustainable Fashion Show In Brighton To Raise Money For Homelessness In City

AllSaints Founder To Host Sustainable Fashion Show In Brighton To Raise Money For Homelessness In City

Chichester Community Warden Helping Fight Against Fraud This Christmas

Chichester Community Warden Helping Fight Against Fraud This Christmas

Wealden Council Calls For Government Rethink On Winter Fuel Payment

Wealden Council Calls For Government Rethink On Winter Fuel Payment

Snowy Protest At Lewes County Hall Calls For Fossil Fuel Divestment

Snowy Protest At Lewes County Hall Calls For Fossil Fuel Divestment

Local MP Tours Firefighters’ Centre In Littlehampton

Local MP Tours Firefighters’ Centre In Littlehampton

Former Portslade Scout Leader Convicted Of 79 Child Sex Offences

Former Portslade Scout Leader Convicted Of 79 Child Sex Offences